In this article we’ll look into a real options trading strategy, like the strategies that we code for clients. This one however is based on a system from a trading book. As mentioned before, options trading books often contain systems that really work – which can not be said about day trading or forex trading books. The system examined here is indeed able to produce profits. Which is not surprising, since it apparently never loses. But it is also obvious that its author has never backtested it.

To clarify: I’ve selected the system not because of high profit expectancy or clever algorithm, but because it is quite simple and does not need any of the additional data normally used for option systems, such as earnings reports, open interest, implied volatility, or greeks. Which means that you don’t need to call R functions for options math, and you don’t need to pay for iVolatility options data, Zacks earnings, or any other historical data for backtesting the system. The free Zorro version is sufficient.

The book cover praises the system inside: To reduce your investment risk to nearly zero – Achieve consistent high annual returns in excess of 30% – It does not require you to learn fundamental and technical analyzes, deltas, thetas, gamas, vegas or other Greek goblethegooks of stocks or options – It does not require the ability to predict market direction – It does not require stock picking skills – It does not require close monitoring.

All statements with which I, of course, highly sympathize. After all, why would we need Greek goblethegooks when we get annual 30% without them! And here are the (simplified) rules of our strategy:

- Sell a 6 weeks call and a 6 weeks put of an index ETF. Choose strike prices so that the premiums are in the $1..$2 range.

- If the underlying price touches one of our strike prices, thus threatening an in-the-money expiration, buy back that option and immediately sell a new option of the same type, but to a further expiration date, and a premium that covers the loss.

- Wait until all options are expired, then go back to 1.

If you have a bit experience with options, you’ll notice that rule 1 describes a strangle combo. And you’ll next notice something strange with rule 2. Right, such a system can never lose, since any loss would apparently be compensated by the premium from the new trade. Have we finally found the Holy Grail, an ever-winning system?

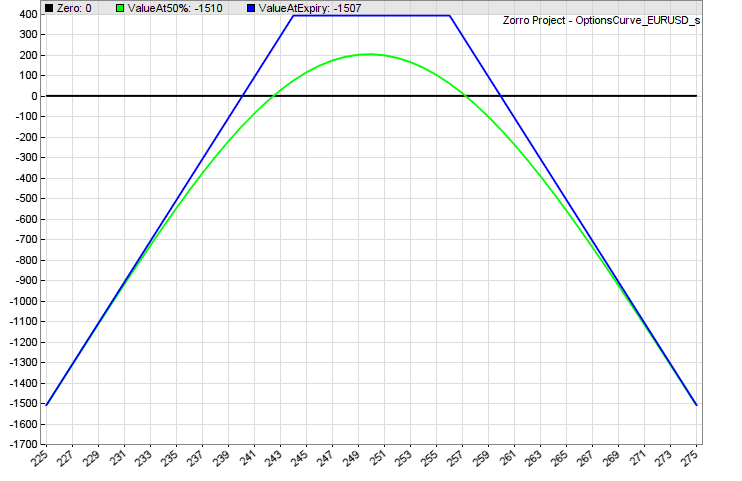

Strangle profit

For getting an impression of the profit and risk, let’s first check the gain/loss diagram of the 6-week $2 premium strangle. This is the definition of a strangle in the curve plotting script from the last article:

// Strangle

void combo()

{

optionAdd(1,SELL|CALL,6);

optionAdd(1,SELL|PUT,-6);

}

The $6 strike-spot distances have been chosen for $2 premium from a hypothetical index ETF with $250 price, multiplier 100, and 15% annual volatility. This is the profit/loss diagram:

Our potential gain is about $400 per combo trade, as expected (2 * 100 * $2 premium). But the price of our index ETF should better not move more than $10 in any direction until expiration. Otherwise the loss can quickly reach the thousand dollar zone. This does not really look like “reduce your investment risk to nearly zero”. But wait, we have rule 2, which will certainly save the day! Let’s put that to the backtest.

The system

// Quite simple options trading system

#include <contract.c>

#define PREMIUM 2.00

#define WEEKS 6 // expiration

int i;

var Price;

CONTRACT* findCall(int Expiry,var Premium)

{

for(i=0; i<50; i++) {

if(!contract(CALL,Expiry,Price+0.5*i)) return 0;

if(between(ContractBid,0.1,Premium)) return ThisContract;

}

return 0;

}

CONTRACT* findPut(int Expiry,var Premium)

{

for(i=0; i<50; i++) {

if(!contract(PUT,Expiry,Price-0.5*i)) return 0;

if(between(ContractBid,0.1,Premium)) return ThisContract;

}

return 0;

}

void run()

{

StartDate = 20110101;

EndDate = 20161231;

BarPeriod = 1440;

BarZone = ET;

BarOffset = 15*60+20; // trade at 15:20 ET

LookBack = 1;

assetList("AssetsIB");

asset("SPY"); // unadjusted!

Multiplier = 100;

// load today's contract chain

contractUpdate("SPY",0,CALL|PUT);

Price = priceClose();

// check for in-the-money and roll

for(open_trades) {

var Loss = -TradeProfit/Multiplier;

if(TradeIsCall && Price >= TradeStrike) {

exitTrade(ThisTrade);

printf("#\nRoll %.1f at %.2f Loss %.2f",

TradeStrike,Price,TradeProfit);

CONTRACT* C = findCall(NWEEKS*7,Loss*1.1);

if(C) {

MarginCost = 0.15*Price - (C->fStrike-Price);

enterShort();

}

} else if(TradeIsPut && Price <= TradeStrike) {

exitTrade(ThisTrade);

printf("#\nRoll %.1f at %.2f Loss %.2f",

TradeStrike,Price,TradeProfit);

CONTRACT* C = findPut(NWEEKS*7,Loss*1.1);

if(C) {

MarginCost = 0.15*Price - (Price-C->fStrike);

enterShort();

}

}

}

// all expired? enter new options

if(!NumOpenShort) {

CONTRACT *Call = findCall(NWEEKS*7,PREMIUM);

CONTRACT *Put = findPut(NWEEKS*7,PREMIUM);

if(Call && Put) {

MarginCost = 0.5*(0.15*Price-

min(Call->fStrike-Price,Price-Put->fStrike));

contract(Call); enterShort();

contract(Put); enterShort();

}

}

}

A brief discussion of the code (a more detailed intro in system coding can be found in the Black Book). The findCall function gets an expiration time and a premium, and looks through the current option chain for a call contract that matches these two parameters. For this it increases the strike price in 50 steps. If then still no contract is found at or below the desired premium, it returns 0. Otherwise it returns a pointer to the found contract. The findPut function does the same for a put contract.

The run function sets up the backtest time and other parameters for the backtest as well as for live trading. It’s a daily script, and the function runs every day at 3:20 pm Eastern Time. It uses two historical data files for the backtest. The asset function loads a file with the unadjusted SPY prices (why unadjusted? Because determining the strikes-price distances would not work with dividend adjusted prices). The contractUpdate function loads the SPY options chain of that day, either from the broker, or from a file. Those two files must be present, plus the asset list AssetsIB.csv that contains commission, margin, and other parameters for simulating the broker or exchange where we trade.

The next part of the code implements the miraculous rule 2. It calculates the current loss, closes any position that is at or in the money, and immediately opens a new position, with a premium slightly above our loss (Loss*1.1). This way we’re punishing the market for going against us. The printf function just stores that event in the log, so that we can go through it and better see the fate of those trades.

The last part of the code is the strangle. Note the MarginCost calculation. Margin affects the required capital and thus the backtest performance, so it should reflect your broker’s margin requirement. By default, the margin of a sold option is the premium plus some fixed percentage of the underlying that’s set up in the asset list. But brokers often apply a more complex margin formula for option combos. Here we assume that the margin of a sold strangle is the premium (which is automatically added) plus 15% of the underlying price minus the minimum of the two strike differences. We multiply that by half because we have 2 positions, but the margin formula is for the whole strangle.

The backtest from 2011-2016 needs only about 2 seconds. This is the result (assuming we always open 1 contract):

Monte Carlo Analysis... Median AR 12% Win 3699$ MI 51.38$ DD 935$ Capital 5108$ Trades 93 Win 59.1% Avg +39.8p Bars 24 AR 12% PF 1.84 SR 1.08 UI 5% R2 0.89

We have won about 60% of all trades, and made 12% annual return based on Montecarlo analysis. Not too exciting. What about the “consistent high annual returns in excess of 30%”? And how can we get a $935 drawdown when we always compensate our loss with a new trade?

Is rolling over irrational?

Let’s try the same strategy without the rule 2. This simplifies the script a bit:

// Even simpler options trading system

#include <contract.c>

#define PREMIUM 2.00

#define WEEKS 6 // expiration

int i;

var Price;

CONTRACT* findCall(int Expiry,var Premium)

{

for(i=0; i<50; i++) {

if(!contract(CALL,Expiry,Price+0.5*i)) return 0;

if(between(ContractBid,0.1,Premium)) return ThisContract;

}

return 0;

}

CONTRACT* findPut(int Expiry,var Premium)

{

for(i=0; i<50; i++) {

if(!contract(PUT,Expiry,Price-0.5*i)) return 0;

if(between(ContractBid,0.1,Premium)) return ThisContract;

}

return 0;

}

void run()

{

StartDate = 20110101;

EndDate = 20161231;

BarPeriod = 1440;

BarZone = ET;

BarOffset = 15*60+20; // trade at 15:20 ET

LookBack = 1;

set(PLOTNOW);

set(PRELOAD|LOGFILE);

assetList("AssetsIB");

asset("SPY"); // unadjusted!

Multiplier = 100;

// load today's contract chain

Price = priceClose();

contractUpdate("SPY",0,CALL|PUT);

// all expired? enter new options

if(!NumOpenShort) {

CONTRACT *Call = findCall(WEEKS*7,PREMIUM);

CONTRACT *Put = findPut(WEEKS*7,PREMIUM);

if(Call && Put) {

MarginCost = 0.5*(0.15*Price-min(Call->fStrike-Price,Price-Put->fStrike));

contract(Call); enterShort();

contract(Put); enterShort();

}

}

}

Simply removing the rolling over improved the system remarkably:

Monte Carlo Analysis... Median AR 25% Win 5576$ MI 77.46$ DD 785$ Capital 3388$ Trades 78 Win 80.8% Avg +71.5p Bars 35 AR 27% PF 2.00 SR 0.92 UI 5% R2 0.92

The equity curve with no rolling:

Now the 25% annual return are somewhat closer to the promised profit. Of course at cost of higher risk, since no limiting mechanism is in place. We could now test other option combos instead of the strangle, for instance a condor for limiting the risk. We can run an optimization for finding out how the profit is affected by different premiums and expirations. I leave that to the reader. The interesting question is why rolling over options, not only with this, but with many option trading systems that we have coded so far, reduces the performance remarkably. Often to the client’s great surprise.

Rolling over with loss compensation establishes in fact a Martingale system. And such a system fares no better in option trading than in the casino. In fact, even worse. In the casino you have at least the same chance with every play. In trading, a losing option combo hints that the market starts trending – and the trend is likely to continue with the rolled over contract. Quite soon you cannot anymore compensate your losses with higher premiums, since you’ll find no contracts at that value. Ok, you could then start increasing the contract volume. If you really did that, you can calculate under the link above how long your account will survive. Rolling over a losing contract is typical irrational human behavior – but the markets tend to punish irrationality.

Artificial options data

Since the system does not rely on goblethegooks, we can check whether the artificial options data that we created in the first part of this mini series can be used for testing this system. The backtest results above were with real options data. Here’s the result with the synthetic data:

Monte Carlo Analysis... Median AR 31% Win 7162$ MI 99.49$ DD 1188$ Capital 3866$ Trades 88 Win 81.8% Avg +81.4p Bars 30 AR 31% PF 2.36 SR 1.12 UI 4% R2 0.88

It’s similar, but not quite identical to the real data. Artificial data represents a more efficient market situation, since its option premiums are identical to their theoretical values, and fundamentals such as earnings reports play no role. You can use it for confirming the real data backtest. Or for saving money, by backtesting a non-goblethegooks system (yes, I like this word) first with artifical data, and only if it looks good, purchasing real data for the final test.

I’ve added the full script to the 2017 repository. You’ll need Zorro version 1.73 or above. You can find the unadjusted SPY data in the History folder of the archive (alternatively, download it with the Zorro command assetHistory( “SPY.US”, FROM_STOOQ | UNADJUSTED)). If you don’t want to create the artificial 2011-2016 options history yourself, you can download it from the historical data archives here.

Conclusions

- Mind the margin cost in backtests.

- Do not roll over losing contracts.

- If your system has no goblethegooks, try artificial data.

Literature

(1) is the book from which I pulled the system. The book is ok – not better or worse than most other options books, but at only $10, getting it is no mistake.

(2) is a really good introduction into the options trading matter. Even though its author shamelessly plagiarized the title of my blog, and this even years before I started writing it!

(1) Daniel Mollat, $tock option$, BN Publishing 2011

(2) Philip Z Maymin, Financial Hacking, Wspc 2012

Great stuff!

Really enjoyed your article!

jcl,

Do you know of any options systems based on *buying* options and exploiting their upside?

Yes, many systems buy options as part of a option combo. For instance, a butterfly or condor involves buying options.

thank, will try it at home

The explicit MarginCost is only calculated before new trades are opened. What about the MarginCost for currently open trades? The manual states it is provided by the broker but in test mode? It seems to default to something derived from the assetList() which appears to be wrong: the explictly calculated MarginCost varies approx between 10 and 15 while the implict one is ranging between 80 and 100 (with my Assets file).

So I thought the script required an explicit MarginCost calculation for each bar and adjusted the code, see below. However, this does not change the capital requirements at all – why not? Is the MarginCost implicity overridden? And if yes, is that correct?

…

var Price,StrikeCall,StrikePut;

…

// all expired? enter new options

if(!NumOpenShort) {

CONTRACT *Call = findCall(WEEKS*7,PREMIUM);

CONTRACT *Put = findPut(WEEKS*7,PREMIUM);

if(Call && Put) {

StrikeCall = Call->fStrike;

StrikePut = Put->fStrike;

MarginCost = 0.5*(0.15*Price – min(Call->fStrike-Price,Price-Put->fStrike));

printf(“\nInitMarginCost %.3f – Price %.3f”,(var)MarginCost,Price);

contract(Call); enterShort();

contract(Put); enterShort();

}

}

else {

MarginCost = 0.5*(0.15*Price – min(StrikeCall-Price,Price-StrikePut));

printf(“\nMaintMarginCost %.3f – Price %.3f”,(var)MarginCost,Price);

}

MarginCost is not the margin of your account. It is a position margin and set up before opening the position. For changing the maintenance margin of an open position, use the trade variable ThisTrade->fMarginCost.

Thanks, I have now tested manipulating ThisTrade->fMarginCost and I see also an expected effect on capital requirements. However, after setting ThisTrade->fMarginCost MarginCost still has a different value. Maybe you could elaborate how fMarginCost relates to MarginCost? Thanks again.

found it:

#define MarginCost g->asset->vMarginCost

So it is just the asset’s default margin.

I assume the individual trade’s margin requirement will remain unchanged during the life of the trade in test mode – unless actively set via ThisTrade->fMarginCost, sorrect?

Yes. MarginCost affects ThisTrade->fMarginCost, but not vice versa.

Dear jcl

Great content as usual.

Don’t publish this comment, please.

Just wanted to point out a typo: “goblethegook” should be “gobbledygook” resp. “gobbledegook”.

Well, nice exercise, only that such a system would not work in the real life. The market was very calm in the tested period. If a crash occurs, at it eventually always does, the market falls 10 or 30% % a day, the implied volatility soars 10 times, you end up heavily in the money by the end of the day, and you lose more in one day than you gained in 10 years.

@Jan: It is exactly due to such kind of assumptions why the system actually works: a tendency to overestimate & overprice (tail) risk. Testing this indeed very simple system with real historical data (EOD) shows a drawdown of approx 3 years profit which recovers after another 3 years. Of course a very heavy drawdown but much smaller than you thought. And it gets a lot better if you slightly optimize the system by e. g. picking options by delta.

the drawdown I’m referring to occured in 2008, of course

Have someone tested out this system with the last volatility implosion data from a week ago?

The same system more simplified is using a positive break-even stop on a trade. In more detail: When a trade is made after a certain value a stop is moved to break even usually plus a few points.pips.dollars.

This option trading method described in the blog loses out on the opportunity to profit from a trend.

We normally do not use trailing stops on options, because systems often perform better by letting contracts expire. But you’re free to test it, a trailing stop is only a few additional code lines.

Great post jcl!

One question: it looks like you are not closing your options just before expiry (as some do), but just let them expire. What happens when you do get assigned SPY shares on Fridays (usually after the cash market has closed) – do you sell those shares on Monday mornings?

Yes. By default, the system sells any underlying position immediately when the market is open, and books the profit or loss to the account.

Amazing content. Thank you for publishing.

Just a suggestion regarding a slight modification of the second rule of the system noted above. Instead of rolling out (to a later expiration date) the “tested” leg of the strangle (ie, the strike price the underlying touches), you roll down the “untested” leg of the strangle (ie, the strike price that is now furthest away from the underlying). The modified second rule would be as follows:

(2) If the underlying price touches one of our strike prices, thus threatening an in-the-money expiration, buy back the OTHER out-of-the-money open option and immediately sell a new out-of-the money option of the same type, with the SAME expiration date, closer to the ATM/ITM strike that is at a premium that covers the loss.

The reasoning behind this type of adjustment is that you take profits on the untested side (OTM option) and give the underlying time to move away from the tested side (ATM or ITM option). The additional credit you receive from rolling up/down the untested side helps offset the loss from the tested side. However, this sometimes results in an inverted strangle.

Just found the site and very impressed with the content. Thanks again.

This is an interesting idea, and should in theory indeed produce a better result than the original rolling under the assumption that trends are continuing. I’ll test this when I got some time.

One problem I get working with options on zorro is that exitTrade(ThisTrade) and exitShort() don’t seem to have any effect. Reading the log shows that they always expire for a price. I’m using these guides to put together a simple covered call system (prelude to something more interesting). Unfortuntely, JCL seems to provide the best guides, meager though they are, on how to use zorro with options.

There are indeed not many guides about algorithmic options trading. But I think this is an issue with the C language, not with trading. If your script does not behave or does not exit as it should, the best place to get help is the lite-C forum.

Hi,

could you help me with the problem:

I want to add in my strategy hedge with buying put option 1$ lower than I have sold put , but I have syntax error in function

CONTRACT *Put2 = contract (PUT, WEEKS*7, Put->fStrike-1);

where is my mistake ?

I cannot see a syntax error. Maybe something is wrong in the previous lines. This blog is anyway not the best place for coding help, but post your script in the Zorro user forum. It should be no problem to find the mistake.

Algorithmic trading

has revolutionized currency equities and bond markets globally, making them more efficient. In developed markets such as the US, it stands at approximately 70- 80% of the equity market turnover. Algorithmic trading in India has also increased up to 49.8%

Hey guys!

This stuff is incredible! I just read through algorithmic options 1-3 and really find all of this very interesting. However, I am very new to all types of coding and was wondering if there is a walk through video on how to input the code into a brokerage account and let it trade on its own? Any help is appreciated.

Thanks

Learning to code is difficult with a video, so you normally learn it from a book and by doing it. There is a small coding tutorial in the Zorro manual and a bigger one in the black book.

Great analysis. Algorithmic option trading is the future.

JCL,

thank you for a very good quality analysis of option trading. I think a combination of short and long options could greatly improve delta/gamma standing and potentially could bring better results. It would be nice if you could make an article on ratios and delta hedging with a code example. I think it would be a great value for all community.

Really appreciate your opinion.

Thank you very much in advance!

Thanks – I’ll certainly consider your suggestions when I do a 4th article on that subject.

As far as I know SPY-Options are american style and therefore come with the possibility to be exercised anytime. The deeper they are in the money the higher the possibility of leaving you with losses and an undesired ton of ETFs to be sold for comission. Additionally this would pulverize the advantage of selling put and call at the same time as both can be exercised at different points during the life time.

Are those aspects covered by your tests or does this system only work for european style options?

You’re right that SPY are American style options, but you got the “pulverizing” the wrong way around. It happens rarely that options are prematurely exercised, but when it happens, it’s usually good for the seller. It reduces loss or allows to collect profit early. We have another system that sells ITM options, and that one gets premature exercising relatively often, when the buyer hits some loss limit. You then close all, book your profits, and enter the next combo. Premature exercising will normally produce a bit more trades and a bit more profits.

You can simulate that in the backtest when you assume a certain model of the option buyer’s behavior, like establishing a loss or profit limit. Then you’ll see how premature exercising affects your returns.

Great!

jcl. I see significantly better returns using the artificial options over the real data. Can I trust the results?

Unless the difference is caused by using strikes or expirations not present in the artificial data, you can trust that you better use real data for that asset and strategy.

I’m sorry. I didn’t understand the last part.

you can trust that you better use real data for that asset and strategy.?

If your strategy or asset produces significantly different returns with artificial data, you’ll need real data for testing it – I think that is obvious.

Have you used machine learning for options? Does it make sense?

We did it, but with mixed results. Options expire only once a week. That’s normally not enough data for predicting returns, or predicting the price at expiration. Options selling or buying is a trading method where machine learning cannot provide much advantage.

Hi -thank you for the article – i found it useful and interesting one

I wonder if combining in the rolling mechanism a 3rd part which is rolling down (strike wise)

the “winning leg” can improve the results

Also the observation about the directional trending behavior of the underline asset is in place

but i found out that using the same mechanism on short calls that been pierced (breakout in the underline) can be useful to the sense that you can roll it up in strike and out in time while enjoy the theta decay -in that case the short call act as a p&l buffer to the underline moves

Hi jcl, how can i get the spya.t8 data you use in the test? thank you

You can generate artificial options data with the script from a previous article, but you don’t need that for SPY. You can get real SPY options data from the Zorro website.